As you will learn, ruby, sapphire, and emerald have romantic histories that link them to the rich and famous. But other, lesser-known gems might also attract consumers’ imaginations from time to time.

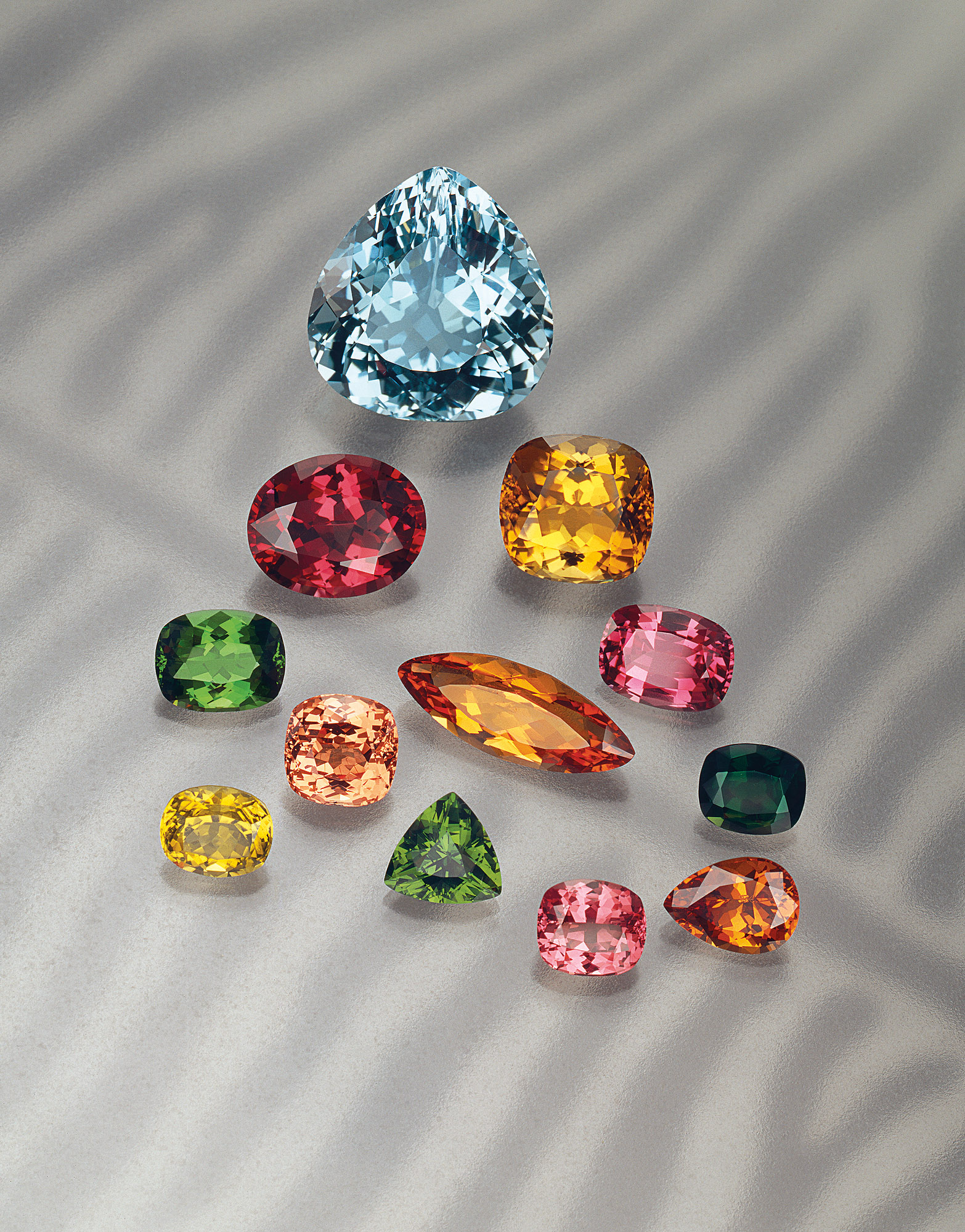

Gem colors pass in and out of fashion just like clothing colors do. Warm earth colors, russet browns, and peach shades, in gems like citrine and zircon, might be in favor temporarily to complement a season’s fashions. Delicate pastel shades of peridot, aquamarine, and pink tourmaline might be one year’s favorites, only to be replaced by stronger, bolder primary colors the following year.

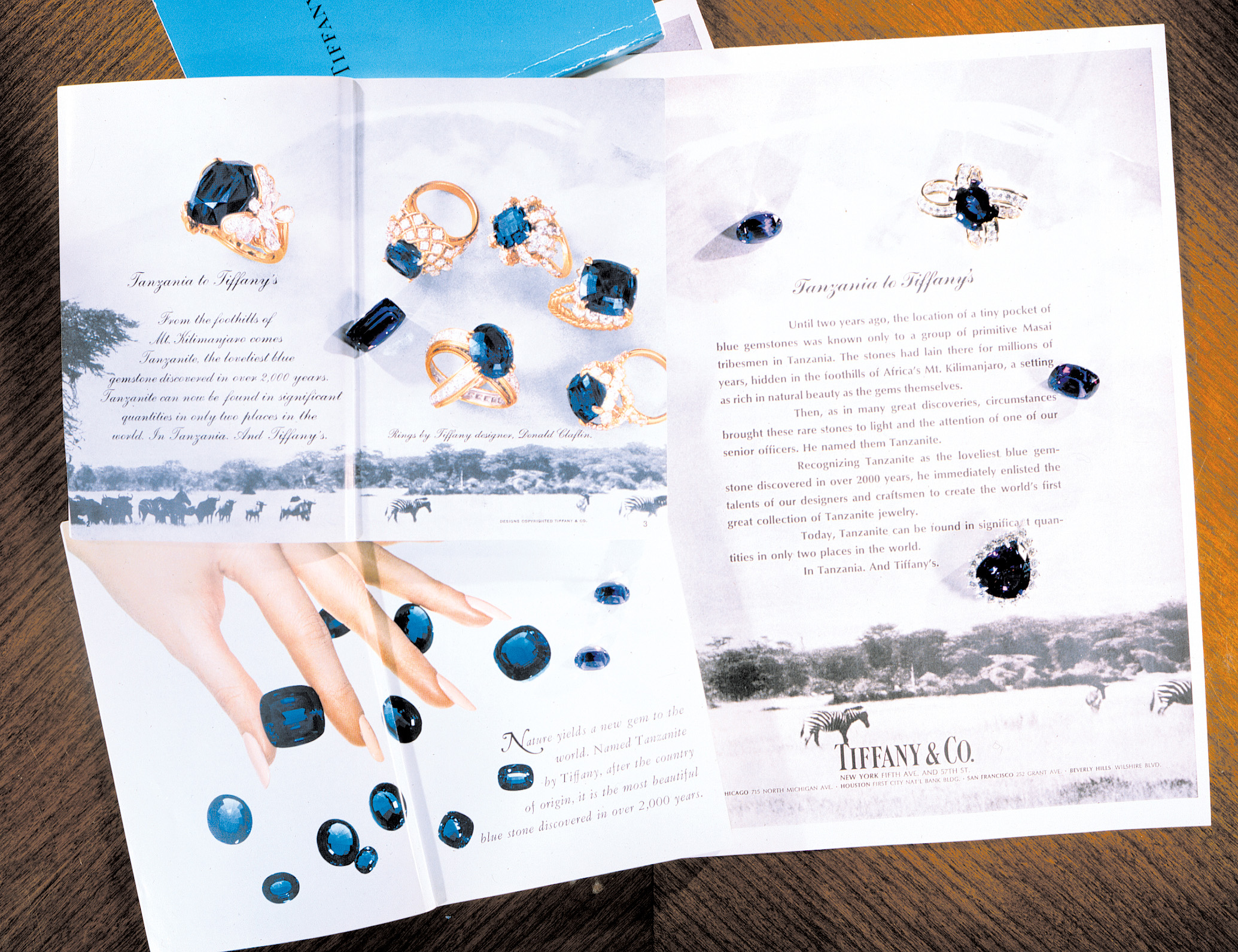

Sometimes clever marketing can greatly boost a gem’s popularity. For this to succeed, the gem must be available in sufficient quantity to market, and it must be sufficiently attractive—or have some special quality—that consumers will find desirable. It must also have a name that’s marketable and easy for consumers to remember, or its name must be already well established, like ruby and sapphire.

The history of tanzanite can help you understand the relationship between supply, demand, and marketing. The gem is an attractive blue variety of zoisite that’s mined in the African country of Tanzania.

An upscale jeweler invented the name tanzanite in the 1960s to market the gem as an alternative to fine sapphire. The association with the famous jeweler added status to the gem’s highly marketable name.

Unfortunately, tanzanite had only a single source, so its supply was easily upset by external events. In the 1970s, the Tanzanian government took over the mines, and supplies declined considerably.

At first, because demand for the gem was still strong, prices rose as wholesalers competed for the diminishing supply. Less tanzanite reached the consumer, and retail prices increased sharply. When prices reached a certain level, consumers resisted paying the price, and promotion of the gem stopped. Tanzanite slipped from public awareness and became a gem sought by only a privileged few.

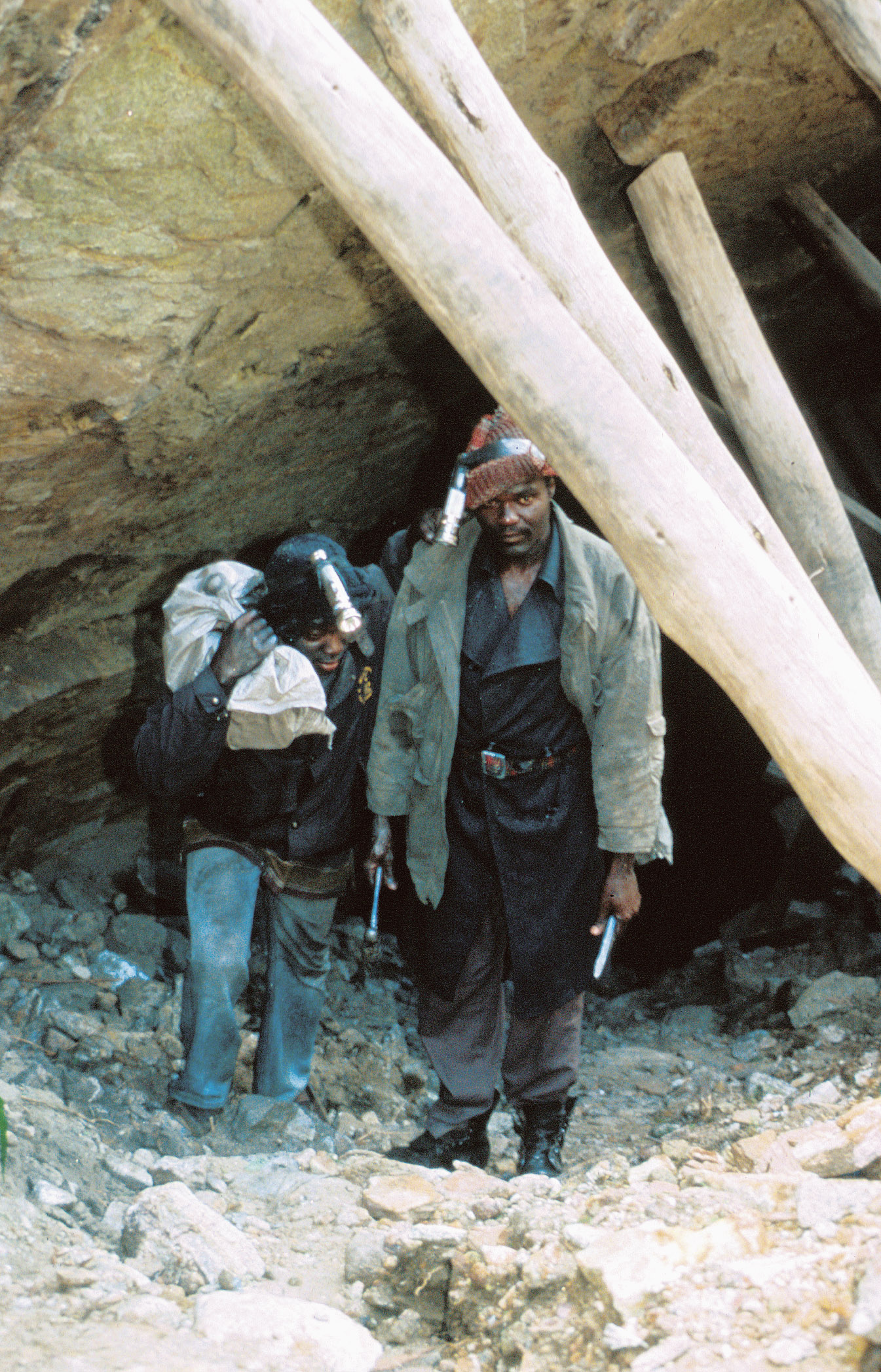

In the 1980s, the Tanzanian government lost control of the tanzanite mining area, and thousands of independent miners swarmed in. Chaotic, illicit mining—unauthorized by the owners of the land—became rampant, and large quantities of small, inexpensive tanzanites were readily available. Supplies of the gem burst back onto the international gem market. Previously high prices plummeted in the face of an abundance of stones.

Supplies and prices stabilized in the 1990s, and demand returned. Gem marketers embraced tanzanite and enthusiastically promoted tanzanite jewelry. Television home-shopping channels introduced tanzanite to millions of US homes.

In the late 1990s, tanzanite mining conditions worsened. Sudden rains in 1998 brought catastrophic flooding that drowned many miners in underground tunnels. This was followed in 2002 by rumors that tanzanite was financing terrorist activities. This was later proved false, but it interrupted supplies of the gem once more.

Since then ownership of the tanzanite deposit has changed several times, and it’s currently under the control of the Tanzanian government and private investors. You’ll learn more about these changes and the current tanzanite market in Assignment 21.